THANKS

NIROX Foundation, Benji Liebmann, Mary-Jane Darroll, Beathur MGoza Baker, Allen Laing & Heidi Fourie, John Nkhoma, Maria Mwase, Stephan & Tammy Du Toit, Trent Wiggle, Niel Nieuwoldt, Prof. Francis Thackery, Prof. David Lewis-Williams, Prof. Bernhard Zipfell, Dr. Sarah Wurz, Dr Mpho Matsipa, Manthe Ribane, Mada Sthembiso, Pieter Burger, WAKE, VATIC Film, Brett Rubin & Nicole Van Heerden, Tom Glenn, Kieron Jina, Joni Barnard, Mametja Moshe, Solly Tsmamabolo, Ted Moyo, Artist Proof Studios, Kim Berman, Sara-Aimee Verity, Nathi Nladla, Dumi Sani, Bevan de Vet, Danie Nel, Didier & Fiona Presse, Anthea Pokroy, Kayombo Magadla, David Adjaye, Jonathan Liebmann, Shruti Nair, Colin Dalton, Prof. Minhyong Kim, Dr. Dominic ffytche, Dr. Balazs Szendroi, Aymeric Peguillan, Richard Forbes & Kate Bailey, Angus & Reena Taylor, Alex von Klitzing, Francis Goodman, Ruann Coleman, Anna Nordquist Anderson & David Svensson, Mohau Modisakeng, Hannelie Coetzee, Primitive Magazine, Akira Wang, Daniel Liebmann, Monna Mokoena, Anton Taljaard, Helen Pheby, Carrie Scoville, ERJ

17.3.15

Arriving just ahead of sundown at O.R. Tambo airport, I wait in the limbo zone before security and take the opportunity to put some thoughts down while I am still on African soil. Thinking back to the opening of ‘Altered States’ a few nights ago, in my mind’s eye I go over the experience of walking around the space after the opening, alone with the work that I had installed there: the flyers advertising penis, breast and buttock enlargement on the pillars; gun related graffiti, signs and tags; drill marks in the floor that uncannily echo the marks in the stone, masked spray marks that riff with marks in the prints; harsh expanses of flaking dry concrete and peeling paint; the countdown of workstation numbers that string a rhythm around the space; the incessant stream of traffic crossing the overpass; a spatter of blood on the wall in the space where the party was held; the stench of burning plastic mingling with the sweet scent of food and sweating rubbish on the night air; and close-by the sound of a late bar pumping a deep throbbing beat that I can feel in my solar-plexus, are all part of what is already coalescing into a memory. It seems to me that the space was a fitting counterpoint to this body of work evolved in the openness of the bush, in the Cradle of Humankind

My residency at NIROX has been an extraordinary opportunity to experience first hand how our evolution as a species has been supported by the geophysical environment within which those changes may well have happened. Also, how the constants of nature have had an influence on the development of our consciousness and continue to do so. Looking at the way we are making now in the digital moment it doesn’t seem so far removed from those early marks. We are still working with the same fundamental forms that are constants of nature, or rather those constants are working through us. As a result of engaging with the materials of the place – of thinking, through engagement with materiality – I have been able to go deep into the condition of the site. Rather than having arrived at any definitive conclusions, it feels like questions have been posed and a conversation started

A lot of South Africans have been asking me during my time here if I have been to such-and-such a place to which I have always answered no, because I have simply moved on a path between the Cradle of Humankind and Johannesburg for nearly five months. Backwards and forwards – the route between the two locations acting like the energetic bond between two atoms – the sum of which is billions of years of planetary evolution. My time in South Africa somehow reminds me of a book I read many years ago – ’The Rings of Saturn’ – where the protagonist meanders on an internal odyssey whilst on a walk of more prosaic proportions. I know that I have travelled nearly to the other side of the world to be in Africa but since being here I have attempted to focus my attention on getting to know the relationship between the deep geological past that is so palpable in the Cradle of Humankind and the present reality of the continents main city. I have travelled a fair bit in my life so far but I have felt something in South Africa that I have not experienced to such a degree before – that of a sense of potentiality or immanence – Africa may well be our past but my intuition tells me that it is also likely to be our future

15.3.15

12.3.15

Tomorrow the show opens at Hallmark and there is still a lot to do. Solly drove by NIROX after picking up Mada and Manthe and we went into town together. Every journey into Johannesburg that I have taken in the past months has taken me past Zandspruit informal settlement. What would formerly have been known as a township – now supposed to be called an informal settlement or simply a ‘location’, Zandspruit is a highlight of the journey for me. Colourful signs and graffiti adorn the sprawling but tidy assemblage of zinc-clad shacks and lean-tos that border the eastern side of the road and spread down the hillside for many acres. Early in the mornings and late in the evenings, the lanes throng with people on their way to, or coming back from work. Most of the rest of the time, from the my perspective on the outside, the whole place has looked like a constant party, with crowds of brightly dressed residents gathered in groups talking, shopping, hanging out listening to music and walking the red earth roads and alleyways that thread through the settlement. For me, Zandspruit and the glimpses that I have had of the Central Business District of Johannesburg feel the closest to the idea of ‘Africa’ that I had before actually being here. Interestingly, any attempt to pull up a Google maps road view of Zandspruit doesn’t yield any results

We had left in a rush and were running late but all agreed that it was a false economy to keep going without any breakfast, so happily for me we pulled over in Zandspruit. I had been warned off stopping here, allegedly due to the history of aggression from the residents and the strong history of protest associated with this location, but the welcome that I received, as ever, was completely the opposite to any that I might have been led to believe. We drank strong sweet tea and ate doughnuts with mango pickle and avocado. It was a solid working breakfast and we drove off needing to work

When we got to Hallmark Towers, the prints had just arrived from the framer. As I worked with MJ and Neil to hang the beautifully framed images, Manthe and Mada went through the first stages of ‘Bassline’ inside the metal framework, yet to be filled with a tonne of red soil from the site in the Cradle of Humankind where we have been practising up until now. As we made the final decisions on the sequencing of the works on paper I went over to watch them working through the final sequence for the performance. In the days since we had last met, we had been in close conversation about how we might evolve the last moments of ‘Baseline’ so that they embody movement that will – in conjunction with the constant binary on-off of the stroboscopic light that will be sole illumination for the work – have a digital quality. They quickly went through a sequence of material where they stood side by side breathing for a few moments, then followed a series of swift movements with their hands and arms that described a geometry of points and lines in, and out into space after which Manthe slumped to the ground. After another moments pause Mada left the space walking away through what would be the audience, followed by Manthe lifting herself off of the ground and exiting from the performance space in the opposite direction. It was complete

Mada and Manthe then worked through the piece from the top to the bottom, inhabiting the dimensions of the space. Pieter arrived with his colleague and we went through the final fittings of the tailored body covers. The geometric grid pattern looked extraordinary as it expanded and contracted over the contours of their bodies. Pieter marked the openings for the eyes, nostrils and mouth on each of the head covers to take away then deliver back in time for the opening performance. We then worked together to fill the five by five metre steel framework with soil, slowly sieving through to remove thorns and roots and break down any of the large clumps of earth still bound together with moisture. After raking the earth flat it had an incredible quality, expressing light and colour at the same time as it absorbed it. The transferral of this primary material from its original location to this new urban context seems to accentuate its inherent qualities. Finally the strobe light is fitted, centred above the square of earth

10.3.15

Trent and his team arrived with their truck equipped with a crane capable of lifting five tonnes at ten in the morning just as it beginning to get hot, to sling and lift the finished sculpture from its home of three months. The slinging is a complex procedure and I am grateful for Trent’s experience and diligence. The weight distribution in the boulder is hard to judge and I feel an immense sense of relief when the five tonne block parts company from the bearers that have been supporting it and lifts up into the air

After the sculpture was safely strapped to the bed of the truck, we drove into Johannesburg to the exhibition venue at Hallmark Towers. Johannesburg is one of the most wooded cities in the world, and as we drive over the ridge and look out to the south, the city rises shimmering in a late summer haze from its astonishing green foundations like a Ballard-ian construct

At Hallmark Towers the slow process of getting the work into the space started by unloading the sculpture onto the street. At that point a fifty metre traverse of an alleyway using two two-tonne pallet trucks, brought the work to the foot of the ramp leading up to the exhibition space. From there, Trent’s team used a complex sequence of rigging with ratchet straps and slings and deft control of the boom of the crane to navigate the incline. On the other side of the exhibition space, Allen Laing and I had been working to assemble the steel framework for ‘Human Nature’ and drill and fix the steel perimeter framework for the performance space to the floor. Four hours later, the massive stone sat poised at the threshold of the room

The floor at Hallmark Towers is only rated to carry a three-hundred and fifty kilogram point load, so after negotiations with the engineers overseeing the space some days earlier, a web of scaffolding had been established in the shop underneath the area that the boulder had to pass over to get to its location. The pallet trucks were employed to roll the sculpture across the floor and after hours of jacking, levering and wedging, ‘Changing My Mind’ was in its place

Even though it was poorly lit by the orange glow of the sodium street lamps filtering in from beyond the overpass and through the traffic-grimed windows, in the early hours of the morning the work hummed as it seemed to levitate off the floor. When I was making the work at NIROX, it had been supported on two massive timber bearers that kept it a fair distance off of the ground. Here, the work sat on three small points of connection directly onto the floor tiles marked with years of use, and for the first time I saw the way the boulder was loaded so that a large section of the block looked like it was defying gravity. The amount of space underneath the sculpture coupled with the whole form seemingly impossibly balanced on three points, resulted in conveying a powerful sense of density to the sculpture

On the the hour drive back to NIROX with Allen we stopped, exhausted, at a late-night takeaway. Eating our meals off of the bonnet of his pick-up, we were questioned and then frisked by police doing their rounds of the suburbs. I produced one of the small adjusted stone components from ‘Human Nature’ by way of explanation of what we had been engaged in. The cops looked intrigued, passed the object between them turning it over and over in their hands, then passed it back, got in their car and drove off

9.3.15

Just before John and I finished polishing the last of the two hundred-plus concave forms in the surface of the two planes, the sun dipped below the horizon. As we finally circled the boulder looking at the finished object, the space was filled with a barely audible whirring sound as hundreds and hundreds of small insects spun around the white room. Every surface was covered with a field of arched tremulous bodies, wings vibrating incessantly. It carried on like that all night as I sat looking at the stone. In the morning they were all gone. Piles of wings were strewn over the floor and any flat surface – of the insects themselves, there was no sign

8.3.15

The past days have been chaotic as my performance collaborators Kieron Jina and Joni Barnard have had to pull out of the performance due to the constraints of their teaching and performing schedule limiting the moment of time that they can dedicate to our collaboration. With the help of curator Beather MGoza Baker I have been involved in the search for two new performers who might be interested in participating in the work. Beathur arranged a meeting with two Johannesburg-based dancers, Mada Sthembiso and Manthe Ribane. We met in Bramfontein and had lunch whilst a ferocious storm ravaged Johannesburg. Water gushed out of downpipes and the streets were flooded with rhythmically pulsating, fast flowing sheets of deep water. Mada and Manthe get the idea immediately and we were soon talking about how and when we would meet to evolve the piece

Two days later Manthe and Mada come out to NIROX and we walk out to the practice area in the bush. The red earth is cooking by the time we get there but we mark out the perimeter of the square and progress swiftly. The core form of the performance is in place as a result of the intensive sessions already completed with Kieron and Joni. Mada and Manthe quickly become accustomed to the flow of the grid drawing, then they start to improvise. Mada proposes a leg extension and repositioning of one foot behind the other that gives the drawing of the grid a new cadence and complexity without over-complicating it. For me it is an extraordinary experience working with people whose bodies are their medium. To be able to provide a verbal description of a complex sequence of movements and see them almost immediately enacted is somehow miraculous. I can’t help but see a relationship between the language of static sculptural form and that of the body in terms of how each body has distinctive material properties and potentialities that are unique to it and as a consequence imbue the overall work with a particular feel

After Mada and Manthe had the line and point drawings down, we focused on the transition into a reference to contemporary trance dance culture. The line and point articulation has been conceived so that the postures held at each breath have a correspondence to my subjective interpretation of traditional trance dance culture as it was and still is practised in southern Africa. Working with Kieron and Joni previously, we had talked at length about the global phenomenon of contemporary trance dance culture typified by large gatherings of people who dance for days on end, typically at outdoor venues. Now working with Mada and Manthe, I have realised very quickly that the concept of trance dance that I am familiar with and that I had been discussing with Kieron and Joni is more typically a white, Western phenomenon. Maybe one of the main differences between this and the discussion that I am now having with Mada and Manthe is that the Western trance dance experience is often, though not exclusively, augmented by the use of psychotropic substances. Typically, African trance dance is less reliant on the use of stimulants to achieve trance states. That’s not to say that it doesn’t happen, but that it is just less central

Manthe has worked in collaboration with experimental South African outfits like Mafikizolo, Toya Delezy, Spoek Mathambo, OKMALUMEKOOLKAT and Die Antwoord, to name a few. Touring as a dancer with Die Antwoord – internationally recognised for their aggressive rave hip-hop style – has exposed Manthe to the Western dance scene and puts her in a good place to evolve the movement I seek

Mada talked about his memory of being a child growing up in Soweto where impromptu dance battles would start up in the street and spread like wildfire. He remembers dancing on the zinc sheet rooftops of the houses – jumping from rooftop to rooftop as the party of dance-offs and jams moved around the township until the early hours of the morning. Dancing is so central to African culture and identity. When South Africa is entered into a Google search the first art form to surface is dance – particularly street dance. Mada is part of a collective called Shakers And Movers, who have received international acclaim for their high energy blend of moves, humour and social commentary. The music driving their performances is a fusion of Kwaito, hip-hop and R&B focused through the lens of Pantsula – a form of dance that has been around since the 1950s and can be seen as an expression of resistance during the political struggle against the Apartheid government, as well as being used to spread awareness about social issues, and is still evolving thanks to the drive of artists like Mada

Pantsula is typified by quick, darting steps in geometric lines with an uneven rhythmic quality. The knock-kneed Charleston associated with American jazz, as well as popping and locking found in American hip-hop are key influences. Pantsula is a Zulu word and translates as ‘waddling like a duck’. This flat-footed move with buttocks sticking out behind the body is commonplace in the dance form. The similarity between these movements and the San rock art images that I was shown at the Origins Centre by David Lewis-Williams is striking

As Manthe and Mada talk through ideas, testing out movements in the heat of the sun, I sit quietly at the edge of the drawn grid and watch, captivated by their process, interjecting as little as possible so as not to interrupt their flow. At one point the energy shifted and a flurry of moves started to link up. Manthe dropped backwards to be caught by Mada with one hand placed where her neck meets her body. Her body was almost horizontal to the ground with knees bent at ninety degrees and the movement forms a striking analogy with the state of complete trance. Mada calmly lifted her up into an upright posture and after a moment of pause the two of them recombine into an complex sequence of footwork that raised a cloud of red earth that hung in the air for a time before being whisked away by a gentle pulse of air rolling down the valley

We take a break in the limited shade of a stinkwood tree and talk about the work. We are all feeling quite ecstatic and quickly Manthe and Mada recover their energy and run through the sequence from top down. The whole routine takes about seven minutes from start to finish. They run through three times and we return to NIROX tired, focused and quietly content with a very successful day’s work

After some lengthy research I have made contact with a designer who is interested in collaborating with me to make the costumes for the performance. In my work ‘Root’, made in Athens in 2013, the male and female performers were entirely naked, now in South Africa this approach doesn’t seem relevant. It makes sense to me that the specific identity of the performers is more ambiguous. In the trance state the body is in a sense left behind, as all attention is focused on the internal experience. I have a feeling that skin tight body covers that extend from head to foot are the way to proceed

The day after the session in the bush with Mada and Manthe, I drive into Johannesburg to visit Pieter Burger to discuss how we might get the body covers made. Pieter (and his label WAKE) was the 2014 SA Fashion Week Renault New Talent Search winner and it is very clear that we share similar conceptual and aesthetic interests. We meet in a coffee shop in Bramfontein and Pieter hands over six metres of thick white, natural looking stretch fabric. I return to NIROX and use the technique of cross-hatch spray paint application to transform the fabric into a complex geometric patterned bolt. The next day I drive back into Johannesburg and drop the fabric with Pieter at his atelier in Bramfontein where we meet with Mada and Manthe to take measurements for the cutting and fabrication of the garments

Today found us all back in the bush for the first fitting. As Manthe walked out wearing the roughly constructed body cover I realised immediately that the pattern wasn’t going to work. It needed to be sharper. On his laptop Pieter showed me samples of other readymade fabrics that might be more appropriate and one immediately stands out from the rest. It is a traditional, tightly woven, herringbone-like pattern of tessellating black and white

29.2.15

For more than a month I have been walking out into the bush every day to get myself into a state of trance. In the late afternoon as the sun’s rays are starting to lose their intensity, I have been going to a spot under the spreading canopy of the same tree where I have been attempting to use controlled breathing and movement to alter my state of consciousness. I have made considerable progress, so much so that I realised that I was potentially putting myself into a dangerous situation. If I did go deep into a trance state or become unconscious, then I could fall prey to the six-metre African rock python that has been seen from time to time just over the ridge from where I was conducting my experiments, or the hyena and jackal that I have seen on many occasions in the vicinity

My motivation for inducing this state of trance is to personally experience the entoptic phenomena around which my work at NIROX is revolving. I want to make some intervention on the planes of the dolomitic boulder that I have been working for the past months with marks that are driven by this experience, which will operate as an allusion to the early human trance dance tradition that has probably resulted in the early human marks that we know of. The two planes that are now cut, resplendent in their mirror polished brilliance, into the form of the rough boulder, have an exactness and artificiality that operates as a reference to the contemporary moment of digital manipulation of, and intervention in, the material reality of the world. I want to find a way of generating marks that pierce the surface of the flat planes creating a third point in this dialogue with materiality that is going on in the stone, that is located at the birth of modern consciousness

I decided that I would attempt to articulate a network of points as accurately as I could with my eyes closed. Everything else about this work has been so exacting – the calculation of the angle of the faces in relation to the pre-existing naturally eroded form of the stone, and the precision ground surface that has resulted. I know that it would be impossible to carve in a trance state, but carving with my eyes closed seems a conceptually legitimate approach in the sense that it is resorting to a different quality of sensing. A sensing, not of measuring, but of intuition and instinct rooted in the sensation of the body

In the afternoon just after the rain has passed, I attempt to make a grid of points as accurately as I can using a hammer and punch with my eyes closed. I am surprised when I find that I can actually swing the hammer and strike the punch with my eyes closed but I suppose that I have been carving for long enough now that it is body memory. I attempt to make each strike with a similar force. The desire to open my eyes part way through is almost unbearable. It is a driven by a profound need to gather more information to complete this task but I managed to resist the temptation

When I opened my eyes I saw a band of marks arcing across a portion of the surface of one face. The grid that I intended is barely discernible but the physical presence of my body is. Each mark has a different effect on the stone – some blows have made the most minimal indentation in the obdurate material, others have flaked off small areas of stone and penetrated a few millimetres into the surface. What is very apparent is the way the array of marks bear the memory of the movement of my arm and hand in a visible series of nested curves

The next day I continued to work the marks in proportion to their impact on the surface of the stone. The stronger the impact, the deeper and wider the depression I open out. I attempted to retain the form of the each impact so that the concavity that resulted embodied the direction and energy of the blow. As the marks got wider and deeper, some started to join up with each other and the constellation of points started to take on a feeling of being a cloud of information

I have been looking at the block for a long time and feel like I know the stone well. I have examined every fraction of its surface in a desire to understand how it was formed and what stories the process of erosion reveals. I began to feel quite keyed up about the new tension that these marks bring to the dialogue in the stone. Now they are opened up, they almost feel like the pressure marks created by someone pushing their fingertips repeatedly into a thickly viscous surface. I have decided that it feels right to file the insides of the concavities smooth and polish them to the same finish as the flat planes

I lay up a sheet of paper on the newly punched surface and make a graphite rubbing of the array of marks. I flip the paper, trace the marks on the other side and use the sheet as a template to transpose the marks from one plane to another. The point where the two planes intersect becomes an axis of symmetry. I repeat the process on the second face. Over the next days I will work with John Nkhoma to polish each form to a mirror finish

21.2.15

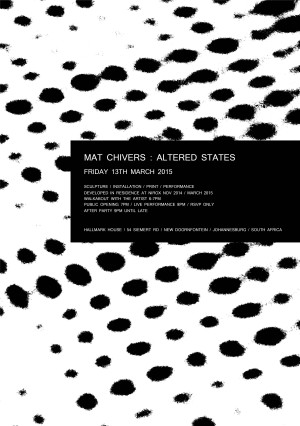

I’ve worked up a graphic for the invitation for the exhibition. We have now fixed on the dates so that the solo exhibition of all of the works made during my residency at NIROX coincides with the launch of Hallmark Towers – the space I first saw with Mary-Jane Darroll some weeks back. The building is being developed by world renowned architect David Adjaye and my show, titled ‘Altered States’, will be the first cultural event in the re-imagining of this iconic piece of architecture

Yesterday I went into Artist Proof Studio, probably for the last time during this session in South Africa, to check over and sign the edition of prints before they go off to the framer. Master printer at APS, Sara-Aimee Verity, has done an extraordinary job of edition-ing the twenty seven images

There are five groups of works on paper. Six monotypes were made by drawing directly into jet black printing ink on perspex plates, which were then printed onto paper while wet, during an intensive day at APS a couple of weeks ago. Around the same time I spent a long day in the studio out at NIROX making a series of ten drawings with a burin into hard ground medium on copper plates. From this group I have selected one plate which was then printed ten times on the same sheet, turned each time in random combination. This process has yielded a series of six unique prints, each the product of ten overlain prints, that demonstrate a subtle shift across the series. The images seem to vibrate with the complex overlay of their cross hatch of lines, creating a shimmering effect that is disorientating to look at

The third and fourth groups of prints have derived from the spray paint drawings that I made back in the first month of my residency. There are five white on black ground and five black on white ground images. High resolution images were made from the large drawings from which positive transparencies were generated in order to allow a darkroom etch into copper plate using a photo-polymer etching process. The reduction in scale from the size of the original drawings has resulted in the loss of some information from the original and the integration of new material into the images as artefacts of the process

The final group of works on paper are the five sheets made with Nathi at Phumani Paper Mill Archive using the material gathered from Plovers Lake cave. It is extremely exciting for me to see these works as they were the ones that I believed had the greatest chance of failing. I simply didn’t know how the materials would shift as they settled down and dried out, as this was not a process that I had any previous experience working with. My main concern was whether there would be a dying down of the vibrancy of the raw materials – in fact the opposite was true

All of the works on paper are united by a common thread. The hand drawn grids of lines are all tuned to the size of the image and there is a gradual shift in the angle of incidence through each series. All of the works have a distilled quality due to their size. Each image is fifteen by ten centimetres on a uniform sheet size of thirty-seven by twenty-nine centimetres and this focused surface gives the prints the intensity that I was hoping for. I wanted them to create a sense of dislocation in the viewer – where the eye tries to focus on a surface or a plane but is not allowed to do so. The images read like small images of big things or maybe big images of small things. I like this sense of ambiguity and the inherently un-quantifiable nature of the source

Leaving APS, I felt a sense of relief that the energy I have invested into these works on paper has resulted in something that feels interesting. I found it hard to pull myself away. It was hard to stop looking, which is usually a good sign. As I waited for my cab to turn up to take me across town I sat in the hot sun on the side of the road and watched the kids pour out of the dance school across the way. They were fizzing with energy and dressed in the most experimental way I have seen yet in Johannesburg. Young adults filtering the influence of western media influence through the lens of a powerful connection to their African culture. It’s a good sight

My cab turned up, I dropped into the seat and we pulled away. As we entered the stream of traffic running around the periphery of the city everything ground to a halt. We were mired in the heat in a traffic jam that could have gone on for ever. We wound the windows down and started to chat. Solly is a student at the business school at University of Johannesburg and he drives for Uber part time to pay his fees and get money to visit his girlfriend who is at university near Botswana. He asks me what I do and I explained a bit and then he asked me if I had been to Soweto yet. I replied that I hadn’t but would like to and Solly suggested that we went then. The off ramp to get there was close so I jumped at the chance

Some time later we were parked up and walking toward the lower end of Vilakazi Street. We had barely set foot on the street when a man jumped out of a doorway and introduced himself. He asked Solly if he was a tour guide to which he replied that he was a cab driver and had offered to show me Soweto as he and his family had always lived there. The man asked if he might interview us for a program that he was making for DSTV about what people love about Soweto. A camera and sound crew erupted out of an unmarked van that we had not seen until then and before we knew it we were being recorded. For my part when asked the question, I replied that I had literally just arrived and so wasn’t really in a position to comment but the way I had ended up there was typical of my experience of South Africa so far. The hospitality and desire to share their perspective of their country was something that I had consistently received from South Africans during my stay

What struck me immediately was how relaxed Soweto felt, despite the horrific history of state brutality and oppression that seems so recent, the single storey bungalows and tree lined streets give the area a laid back feeling that was a refreshing change in comparison to my experience of the hectic pace of downtown Johannesburg. It was getting late so I suggested to Solly that we should go and eat somewhere and asked him where he would normally go. He said that he would usually eat at a local hostel – a roadside place between Soweto and Orlando and said he would be happy to take me there. This was more like it – at last I felt that I was getting a real taste of how the locals eat. We had what is probably one of the best meals of my life. A curious crowd of locals dropping in for a beer after work joined our table as the sun began to set. We ate a plate piled high with slivers of meat from the boiled head of a cow sprinkled liberally with salt. Pap (maize polenta) and a hot chackaalacka salad of tomatoes, raw onion and chilli gave this an edge. Then we ate probably the biggest and best steak I have ever had, seasoned and cooked over the coals of a fire that burns day-in-day-out. I was, according to the man behind the counter, the only white person to have eaten in the place for a very long time